Democracy in Thousand Oaks: The Right to Vote

“The right of voting for representatives is the primary right by which other rights are protected. To take away this right is to reduce a man to slavery, for slavery consists in being subject to the will of another, and he that has not a vote in the election of representatives is in this case”

Christian Vanderbrouk, veteran of the George W. Bush administration and occasional writer for The Bulwark, has been raising alarms of the overtly antidemocratic positions held by the Southern California-based Claremont Institute. [2]

One essay highlighted by Vanderbrouk [3] is penned by Glenn Ellmers, listed by the Claremont Institute as a Salvatori Research Fellow in the American Founding. [4] Ellmer’s article leads in the first section with a frontal attack on America democracy itself with the section title reads:

“Elections—and therefore consent and popular sovereignty—are no longer meaningful.” [5]

Excited about his premise (“This is the big one, and in a way, everything flows from it”), Ellmers advocates that, in our American form of self-governance, “even if conducted legitimately, elections no longer reflect the will of the people.” [6]

These views came after Americans rejected the candidacies of election deniers in the 2022 midterms, but Ellmers doubled down on previously expressed incendiary views.

From an essay the previous year, which starts with the clearly less than subtle sentence: “Let’s be blunt,” [7] Ellmers claimed “most people living in the United States today—certainly more than half—are not Americans in any meaningful sense of the term,” and while he did not “just mean the millions of illegal immigrants,” he was “really referring to the many native-born people—some of whose families have been here since the Mayflower—who may technically be citizens of the United States but are no longer (if they ever were) Americans.” [8]

To Ellmers, “we need a conception of a stable political regime that allows for the good life,” drawing the conclusion that “the U.S. Constitution no longer works.” [9]

The essays prescribe an undemocratic America, where a specific set of values and views should be mandated on the populace, for their and the country’s own good, and to achieve these desired aims, it “would require an alliance in a quasi-political street fight, probably leading to a constitutional crisis.” [10]

While worthy of caution, in a democratic America, this is certainly a minority opinion, and, in my mind, a scary and ugly one. However, as we discussed in our first installment, other far less incendiary factors are used to justify not holding elections at all, since when one holds power, letting others decide is not a natural impulse. There always seem to be reasons for not letting the voters decide.

Truly undemocratic movements can succeed when they find unwitting allies who, for seemingly plausible rationales, support making antidemocratic moves. That’s why it’s important to recognize that democracy is fragile, and it needs shoring up from time to time to prevent these tendencies to lead us down wrong paths.

In this episode, we visit the early 21st century decisions of the Thousand Oaks City Council and how securing our democracy sometimes means placing constraints on those in power. Doing so is at times needed to preserve our right to vote and our political power, which in California we acknowledge “is inherent in the people.” [11]

Edward L Masry, Thousand Oaks City Councilmember (2000-2005) and Mayor (selected 2001)

He was new to the city, but not to worthy battles. Edward Louis Masry established a three-decade long legal career, advocating for a wide variety of clients and being unafraid of controversy. He represented NFL stars such as Roman Gabriel and Hall of Famer Merlin Olsen. He defended television evangelist Gene Scott and took on the state attorney’s general office; when agents handed him an order demanding all financial records from Scott’s church, he and Scott burned the order on television. [12] But one case brought Masry the greatest renown.

Supported by the relentless investigator Erin Brockovich, Masry pursued a multi-million lawsuit against Pacific Gas & Electric for 648 plaintiffs of Hinkley, California, who suffered from the effects of contaminated groundwater. His firm, Masry & Vititoe, joined with two other firms to win a $333-million settlement from the utility, after alleging that the residents of Hinkley had been bathing and drinking water contaminated with carcinogens.[13] The largest settlement of a direct-action lawsuit in U.S. history won Masry attention and accolades as a consumer advocate. Hollywood eventually told the story more widely in the movie Erin Brockovich.

Masry directed his fight to local political causes after moving to Thousand Oaks in 1997. He first contributed $50,000 to defend Councilmember Elois Zeanah against a heavily financed campaign to recall her, a failed effort that spent over eight times that amount. [14] [15] Three years later, he won election to the City Council itself, eventually serving as Mayor and winning re-election with the most votes in city history. [16]

In his first Council run in 2000, detractors attacked Masry for pouring $130,000 of his own money into his campaign, saying this went against the spirit of new campaign finance regulations passed in the wake of the expensive and unsuccessful Zeanah recall effort.[17] However, one charge targeted Masry from another direction: his health. Councilmember Mike Markey, running for reelection to a second full term, sent a mailer to absentee voters subtitled “Honest & Integrity” stating that Masry had a heart problem that could keep him from serving the city. [18]

Markey defended his allegations: “Masry told the Los Angeles Times that he stopped trial litigation because of his health. With dialysis treatment three times a week and three heart attacks in the past six months, how will his health hold up under strenuous City Council work?” Markey said. [19]

The Times stated that they never reported that Masry had a heart attack, and in an interview, Markey would not identify the news articles that did.[20] Masry acknowledged his health problems, including frequent dialysis treatments for a malfunctioning kidney and having heart-bypass surgery a decade prior to unclog arteries, but denied having any heart attacks.

When Masry presented information from his doctor countering the claims, Markey continued sending the mailers, and Masry unapologetically called him out in the characteristically boisterous manner many of his supporters admired. [21]

“How can he say he has honesty and integrity when he was lying and continues to lie?” Masry asked. “I’ll race Markey down T.O. Boulevard for a mile,” he said. “And I’ll drag my dialysis equipment, and still beat him. That’s a challenge.” [22]

Ill health did ultimately meet Councilmember Ed Masry in 2005, the first year of his second term. Following the November 2004 election, Masry had a femoral artery bypass in early March and suffered a series of setbacks, resulting from complications of diabetes and infections from surgeries. [23] Masry missed several meetings that year, spending a great deal of time in the hospital, and aimed to return to the Council that fall. [24]

Masry’s son, Louis, served as his father’s primary spokesperson throughout the year, providing the public with information about his health status and when he’d be able to return to the Council. “He’s anxious,” Louis Masry said. “He talks about it every day, talks about getting to work full time and getting back to the City Council meetings in one form or the other.” [25]

By August, pressure from his political critics began to mount against the ailing Masry, sparking debate about whether he should resign from the Council and free up his seat. Taxpayer advocate Jere Robings called for Masry to step down. “In my mind, it’s just gotten to the point where it seems ludicrous to hold the seat open,” Robings said, referring to Masry’s absence of several months on the Council; according to Robings, there was work to be done and “we need people in there to do it.” [26] According to his son Louis, the talk fired up the elder Masry and had no plans to resign.

The Council unanimously excused his absence on June 21 until he was well enough to return; [27] the decision came with no discussion, said Mayor Claudia Bill-de la Peña, a political ally of Masry’s who joined the Council in 2002 after serving two years as Masry’s appointee to the city’s Planning Commission. Mayor Bill-de la Peña added that she believed the call for Masry’s resignation was politically motivated. “Unfortunately, the political season is beginning, and yes, there have been rumors to find a replacement for Mr. Masry already. It is rather sad that instead of praying for Mr. Masry, there are calls for his resignation,” she said. [28]

Linda Parks, Thousand Oaks City Councilmember (1996-2002) and Mayor (selected 1998), Ventura County Board of Supervisors (2002-2022)

Councilmember Masry did return to the Council in September and attended one additional meeting in October, [29] but his health declined rapidly thereafter, forcing him to submit his resignation from the Council in November.

In his written statement, Ed Masry offered his thanks to members of the city staff, his Council colleagues – current and past – and city residents. He said he was proud of his commitment to public safety, preserving open space, securing financial support for local schools, and advocating for senior issues, affordable housing, and small businesses. “It has been a great honor representing the residents of the greatest city in the world,” he said. [30]

Councilmember Dennis Gillette, who joined the Council in 1998, continuing a tenure in community service with the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department, California Lutheran University, and as an elected member of the Conejo Recreation and Park District, [31] expressed his disappointment that Masry would not be returning to the Council and commended him and his work ethic. “Ed and I had established an excellent working relationship,” Gillette said. “We could discuss openly and frankly issues of importance. I will miss him.” [32]

Ventura County Supervisor Linda Parks, a staunch ally of both Ed Masry and Elois Zeanah, serving with both on the Council during her tenure from 1996 to 2002 before joining the county board, also reflected on Masry’s service, calling her political ally a “no-nonsense straight shooter” and describing him as “a mentor.” “He would always try to move us toward consensus… but he was willing to fight for what he believed in. He enjoys a good debate.” [33]

According to state law at the time, the Council had thirty days to decide on filling the vacancy, where the Council had three options: call a special election, adopt an urgency ordinance allowing for an interim appointment while also calling for a special election, or appoint someone to fill the vacancy for the three years remaining in Masry’s term. [34]

Masry’s son Louis said his father and family wanted a special election and that cost shouldn’t factor in that decision, where estimates of approximately $100,000 had been discussed for holding a special election. “You can’t put a price tag on selecting the right community leader,” Louis said. [35]

The Council called a special meeting for December 2 to discuss their options for handling the vacancy. This meeting was held in the Board Room, a smaller, out-of-the-way alcove in the Civic Arts Plaza, well away from the 400-seat Council Chambers where Council meetings are normally held. The smaller venue seemed appropriate for actions being taken that were perfunctory and not needing significant public input.

Members of the Thousand Oaks City Council handling the 2005 Council vacancy, and the 3-1 split.

From left to right: Andy Fox, Jacqui Irwin, Dennis Gillette, Claudia Bill-de la Peña

The four-member Council of Andy Fox, Claudia Bill-de la Peña, Dennis Gillette, and Jacqui Irwin, who was Councilmember Fox’s Planning Commission appointee and joined the Council in 2004, walked through the alternatives. These included timing options for minimizing election cost impacts; if the Council chose to wait to call the election between December 20 and December 30, the city could consolidate their special council election with the June 2006 election conducted by the county.

Far exceeding the original estimates for a special election and presented to the Council with only days of notice, city staff estimated that a non-consolidated special election would cost “greater than $250,000” and one consolidated with the county would cost $178,000. [36]

Mayor Bill-de la Peña believed that holding an election was the best option. “When there are three years left in a term, it should be decided by a vote of the people, not by appointment,” she said. “Edward has always wanted to let the people decide.” [37]

Mayor Bill-de la Peña moved to call for a special election, one that could be held in June. but Councilmembers Fox, Gillette, and Irwin voted the motion down. [38]

Councilmembers Gillette and Irwin voiced their opinions that they as councilmembers should decide who represents the public. “It wouldn't break the bank, but a quarter of a million dollars is a lot of money and this is an area where I don’t think we need to spend it,” Councilmember Gillette said. “I think the four of us are knowledgeable enough about the needs of the office.” [39]

“That decision is ours,” Irwin said. “The decisions we make, if they’re poor decisions we’ll pay for them in the next election,” adding that a special election would not be fiscally responsible, and she would like to see the seat filled quickly. [40]

The Council majority then voted to open a recruitment process and appoint someone to fill the remainder of the term by mid-December. [41]

Reaction from newspaper editorials was swift and negative regarding the Council’s hasty decision. The Ventura County Star called the decision “questionable,” choosing to “bypass the democratic process and ignore historical precedent” to appoint rather than hold an election, deciding to “take the voters out of the equation.” [42] The Star continued, stating that “current council members weren’t elected to hand-pick who should sit next to them on the dais making like-minded decisions for the next three years. That’s not their job.” [43]

The Thousand Oaks Acorn granted even less deference, stating that “[R]esidents and voters of Thousand Oaks have every right to be infuriated… our city council acted irresponsibly and selfishly regarding the democratic process.” [44] The Acorn continued its castigation of the “illustrious city council in its infinite wisdom” deciding that “three council members know better than the people of Thousand Oaks” who should replace Masry, calling the decision “an insult to the taxpayers of Thousand Oaks and a slap in the face of democracy… The supporters of Fox, Gillette and Irwin – and everyone else in the city of Thousand Oaks – should be embarrassed, sad, angry and depressed.” [45]

Each called out the excuse of money for not holding the election as “dubious” [46] and “poppycock,” [47] with the Star questioning the concerns of election costs being raised by an “affluent city that boasts hefty reserves in the tens of millions and in September voted to dip into its general fund to contribute $250,000 to Hurricane Katrina relief efforts.” [48]

In the words of the Acorn, “A special election should have been mandatory.” [49]

Three days after the Council’s decision to appoint his replacement, Edward L. Masry passed away on December 5, and his life was celebrated by those in Thousand Oaks and beyond. The New York Times and Los Angeles Times captured his life and accomplishments, both in the legal and political worlds. Masry was chronicled as the “flamboyantly pugnacious lawyer” [50] who won a “landmark $333-million settlement against Pacific Gas & Electric Co. for groundwater contamination,” [51] and “was portrayed by Albert Finney in the 2000 movie ‘Erin Brockovich’.” [52] Locally, “his often vitriolic courtroom rhetoric, delivered in council discussions on topics such as flood control basins, sometimes irked local officials. Thousand Oaks land-use attorney [and former Thousand Oaks Mayor] Chuck Cohen, for example, once proclaimed at a council session, ‘Mr. Masry ... you're no Albert Finney.’” [53]

At the December 13 City Council meeting, now held in the larger Council chambers, the Council moved forward 3-1 to appoint Planning Commission Chair Tom Glancy to fill the vacant Council seat; Glancy had been Councilmember Gillette’s Planning Commission appointee. However, some in attendance protested that the meeting was held on the same day as Masry’s memorial services; “I’m greatly offended that you scheduled this on the night of Ed Masry’s funeral. There was no urgency,” said former acting City Attorney Alyse Lazar. [54]

Mayor Bill-de la Peña explained her vote opposing the appointment; “Regardless of who was appointed, I would have voted against them on principle because I’m a fervent believer in having a special election,” she said. “Dr. Glancy is a dedicated public servant ... but the right thing would have been to call for an election, not an appointment, with three years left on the term.” [55]

Council critics attending the appointment meeting suggested that Glancy would create a four-person supermajority on the panel more favorable to development and recommended the Council “extend an olive branch” by selecting someone more likely to promote slow growth, more consistent with Masry’s positions. Councilmember Irwin dismissed the concerns, considering the labels meaningless, and stood by her collective decision with Councilmembers Fox and Gillette. “Everyone on the council is for preserving open space,” Irwin said. “Masry was just like the rest of us; he was slow growth and an environmentalist. But all the council members are supportive of the city's environmental programs.... To say only certain people would mirror his beliefs is untrue.” [56]

Against the “strong preference for a special election to fill his seat, especially since three years remained on his four-year term,” [57] the 3-1 Council majority acted quickly to fill the vacancy themselves. The Council justified their decision, based on their own estimate of $250,000 to hold a special election, but the City later received an estimate from the Ventura County Registrar of Voters that a consolidated election would only cost $50,000. [58] Thus, a hasty decision based on inaccurate information allowed the Council majority to solidify a 4-1 majority on the Council without an election.

Ventura County Grand Jury report on the Thousand Oaks City Council. The Grand Jury made detailed multiple findings and conclusions, including that “there is a perception that many decisions are decided in advance of City Council meetings and that the meetings are essentially a public formality. Three specific examples are: 1) the forced resignation of City Manager Gatch; 2) the recruitment process of a new City Manager; and 3) the decision not to hold an election to replace Councilman Masry, even though three years remained on his term of office.”

Due to the turmoil in 2005 caused by the abrupt resignation of longtime city administrator Phil Gatch and the appointment of Glancy to the Council, these events became the focus of a Ventura County Grand Jury investigation, examining the actions by the Thousand Oaks City Council and highlighting the power dynamics, resulting from decades of tumult in the east county city.

In a strong rebuke of the Council, the Ventura County Grand Jury concluded that the actions of Councilmember Fox “giving specific directives and communications to City Manager Gatch outside a duly-held City Council meeting, pressuring him to resign, may give the appearance of being in violation” of city law and the Brown Act, although evidence of such a violation was “insufficiently clear.” [59]

The grand jury also concluded that “the city government of Thousand Oaks often gives the appearance that it fails to operate transparently and professionally. There is the perception that many decisions are decided in advance of City Council meetings and that the meetings are essentially a public formality,” citing specifically the forced resignation of City Manager Gatch, the selection of a new City Manager to replace him, and the decision not to hold a special election to fill Masry’s vacant Council seat. [60] A “public perception of underhandedness, poor judgment, and lack of professionalism” was evident with handling Gatch’s departure and that the Council’s “history of adversarial relationships, lacks of cooperation, internal strife and acrimony, insulting citizenry, and extreme and disrespectful rhetoric has been well-documented for over a decade.” [61]

The Ventura County Grand Jury investigation served notice that the political environment in Thousand Oaks was in need of change.

Following the community reaction from the Council’s 2005 appointment, the Council briefly entertained an ordinance in 2006 to require special elections when Council vacancies occurred. On reserving the authority to call special elections versus requiring them by ordinance, Councilmember Fox said, “[t]his is a representative government. [The voters] elect us to make decisions. That decision may be to call for a special election, if it’s in the best interest of the city. It may be to appoint a person to fulfill the balance of that term, and this city has done both and they’ve done that over the course of the last thirty-plus years.” [62]

Fox went on to state that adopting an ordinance requiring special elections would undertake a “reckless course,” based upon the “one-time occurrence” of the 2005 appointment to fill a three-year vacancy. [63] Mayor Gillette concurred, saying that “to tie the hands of future councils by modifying the law would be a disservice to the circumstances that they’ll find when they deal with this in the future.” [64]

That future would soon repeat, and the actions of the Council would again rhyme.

In February of 2012, Councilmember Dennis Gillette, after more than 40 years of public service and over 13 years on the City Council, announced he would be stepping down from the dais for health reasons. Gillette underwent several surgeries in 2011 related to diabetes complications and his health issues forced him to miss more than a third of the Council's 27 meetings over the previous year. [65] The parallels between the resignations of Ed Masry and Dennis Gillette were striking: Both missed several Council meetings for health reasons prior to the resignation, and each had nearly three years left on their term when they stepped down to create the vacancy. Additionally, the composition of the Council, even though separated by seven years between 2005 and 2012, was nearly identical: Fox, Bill-de la Peña, and Irwin dealt with the 2005 vacancy; only Councilmember Glancy was new to such a decision. There was one difference, however; in contrast to Masry’s wishes to hold a special election to fill his seat, Gillette encouraged his Council colleagues “to appoint a replacement for my seat in short order.” [66]

Members of the Thousand Oaks City Council handling the 2012 Council vacancy, and the 3-1 split.

From left to right: Andy Fox, Jacqui Irwin, Tom Glancy, Claudia Bill-de la Peña

As in 2005, the Council had three options to handle the vacancy: hold a special election, adopt an ordinance calling for an election and allowing for an interim appointment, or appoint someone to fill the nearly three years remaining on the term. [67] Given the timing of the vacancy, a special election would be held in November 2012, the same time as the general election for city council elections. The costs associated with conducting such an extra election would “be minimal (less than $10,000)... and will be absorbed in the General Fund Budget.” [68]

Given what was characterized as the “botched handling of Ed Masry’s early retirement in 2005,” [69] many assumed that a special election would be the Council’s chosen course, either directly or with an ordinance allowing for an interim appointment. Newspaper editorials pointed out that, based on Thousand Oaks’ previous experience with this issue, “cities should avoid appointments whenever possible. Not only do they fly in the face of democracy, an ideal most Americans hold dear, but they turn into political battles that polarize the general public.” [70]

When the Council met to consider its options, however, it was a replay of 2005, minus any arguments that an election would be too costly; without the ability to hang on election cost estimates of hundreds of thousands of dollars, the Council majority found another self-justification for forgoing an election: time.

Under cover of a legal opinion that the Council may not be able to act quickly enough to allow for an interim appointment and call for an election within the next two months, the Council majority of Fox, Irwin, and Glancy rationalized another nearly three-year appointment. Even though the Council had readily called meetings on 24-hour notice in the past to shrink any timelines and the fact that an ordinance “relating to an election” takes effect immediately, [71] the majority showed no interest in making the effort.

Councilmember Glancy asked, almost rhetorically: “What’s the state say about how long we’ve got to [make a decision]?” [72] The interim City Attorney started to answer with “60 days from…” and Glancy interrupted to close any further discussion with “Thank you, so we don’t really have interminable length of time.” [73] Glancy then moved that the Council progress without an election: “The Council is really elected to make decisions,” so we should “fill by appointment… and issue the application process as soon as possible.” [74]

Mayor Pro Tem Bill-de la Peña pointed out that her colleagues had options if the Council chose to pursue them: “Looking at the calendar, it’s something that would still be doable because we can always hold… a special Council meeting in order to get the ball rolling. We don’t have to wait until the next regularly scheduled Council meeting….” [75]

Mayor Pro Tem Claudia Bill-de la Peña, advocating for an election to fill the Council vacancy, February 21, 2012

Yet, in debating the motion, the majority was determined to move forward with an appointment. To Mayor Pro Tem Bill-de la Peña, this was eerily similar to the 2005 process that was less than open.

“The filling of the vacancy of Mr. Masry[‘s seat] in my opinion set a very ugly precedent,” said Bill-de la Peña. “Thirty-plus applicants from the community were asked to speak for about three minutes before the Council and that happened on the day of the funeral of Mr. Masry who wanted to be replaced by a vote of the people.” [76]

She went further about the lack of transparency then and behind-the-scenes discussions at the time. “I’m saying this on the record tonight – three days before the parade of applicants, I received a call, and I was told who the appointee would be; it was Dr. Glancy, and he was indeed appointed that night.” [77]

To earn the voters’ trust, “I feel a vacancy needs to be filled by a vote of the people,” she said. [78]

In supporting a long-term appointment, Councilmember Fox focused heavily on the nature of electoral campaigns for his justification. “It seems appropriate that we appoint to fill his position,” Fox said. “…Given the height of the political rhetoric that’s already occurred, whoever we appoint needs the opportunity to serve on the City Council in a stable environment and that requires three years.” Councilmember Irwin agreed with making the appointment, concurring with Fox that “my major concern when I’m basing my decision on is the stability of the city.” [79] Bill-de la Peña later reflected that “they say the reason was to maintain stability. It’s not about stability, but about power.” [80]

When evaluating the options, the Council voted 3-1 with Bill-de la Peña dissenting to repeat the same process as in 2005: fill by appointment and hold interviews among applicants. [81] The Council majority eventually selected Planning Commissioner Joel Price, Councilmember Glancy’s appointee, to fill the Council vacancy; Mayor Pro Tem Bill-de la Peña dissented, stating, “I’m for an election in November... I don’t think we need to be afraid of the voters’ decision at all.” [82] [83]

“Why do they fear a vote?” Thousand Oaks Acorn editorial, March 1, 2012.

As in 2005, reaction was similarly blistering. According to the Ventura County Star, “the council botched the decision. Council members should be publicly elected, not appointed, except in rare circumstances. And nothing about this situation justifies an appointment,” noting that “the timing is convenient” to coincide “with the scheduled election of two Thousand Oaks City Council members and the national election… the cost is minimal, about $8,000, and easily absorbed in the city’s general-fund budget, according to city officials… the length of time remaining [on the term] is too great to be filled by a political appointee picked by a majority of the sharply divided council,” and that “the council’s regrettable 3-1 vote reeks of control issues and power politics.” [84]

The Star concluded: “City councils are elected to make tough decisions, but this is not one of them. The council members owe it to their constituents to put the selection of the newest council member squarely in the hands of the voters, where it belongs.” [85]

The Thousand Oaks Acorn started their editorial with the familiar refrain: “‘Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me’… [By] dismissing not one, but two options [for an election], the council majority has again brazenly put its desire to remain in control ahead of this country’s time-honored tradition of voting…. The poor excuses drummed up at last week’s glaringly predetermined vote were offensive to anyone who follows the City Council. The worst: The city attorney’s assertion that the council may not be able to pass an ordinance and select a temporary appointee by April 30, the deadline to fill Gillette’s seat… If there’s anything this council knows how to do it’s move quickly… [and] if it really wanted to pass the ordinance, it would have.” [86]

The Acorn raised a final set of questions: “If T.O. voters continue to remain silent, what’s to stop the council from taking away our voting rights a third time? A fourth?” [87]

When there are disagreements among the people about the direction their self-governance should take, the people must have the ability to drive that direction, and elections serve as a critical component to peaceful and democratic self-determination; elections cannot be considered a convenience that can be dispensed with based on which faction holds power. However, unless the right to vote is guaranteed by higher governmental authority such as state law, federal law, or constitutional provisions, history demonstrates that rationales are often found to forgo elections when it may be in their political interest to do so.

Even in a modern American city such as Thousand Oaks, when a majority of like-minded councilmembers have the opportunity to ignore elections, history shows they will do so unless that discretion is taken away from them.

How can we guarantee our right to vote when a Council can merely dispense with an election? By leveraging the additional checks and balances in our Californian system of self-governance approved a century prior.

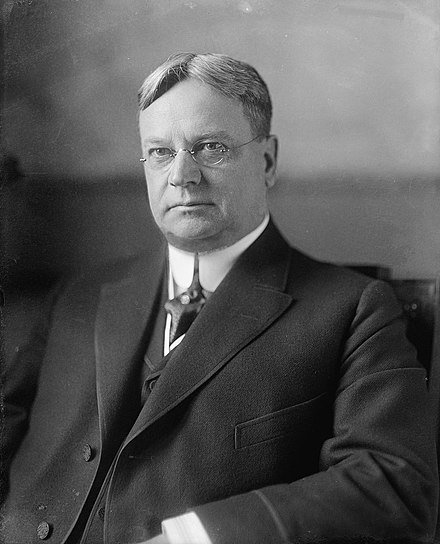

Hiram Johnson, Governor of California (1911-1917), United States Senator (1917-1945)

In 1910, Hiram Johnson won the California gubernatorial election as a member of the Lincoln-Roosevelt League, a Progressive Republican movement, and he helped found the national Progressive Party in 1912, serving as the party’s vice-presidential candidate with former President Teddy Roosevelt at the top of the ticket. Spearheaded by Governor Johnson, twenty-two constitutional amendments were approved by the voters in 1911 and changed the nature of California government, granting women the right to vote, allowing cities and counties to adopt their own charters, and importantly, changing the mechanisms of self-governance.

Governor Johnson gave his reasoning for the self-governance reforms in his first inaugural address: “How best can we arm the people to protect themselves hereafter? . . . We can give to the people the means by which they may accomplish such other reforms as they desire, [and] the means as well by which they may prevent the misuse of the power. . . .The first step in our design to preserve and perpetuate popular government shall be the adoption of the initiative, the referendum, and the recall.” [88]

Initiative, referendum, and recall are considered elements of “direct democracy,” since they grant the people the ability to create, change, and reject laws directly, as well as remove officials from office. Johnson believed the legislatures themselves were too subject to special interest influence and needed a check on them; specifically, Johnson ran for Governor on a campaign to counter the influence of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, described as the “greatest single influence operating in California politics.” [89]

Even with Thousand Oaks having less than five decades as a city, initiatives had been used to regulate the growth of the city, protect open space, and curb urban sprawl. This time, it would be used to protect our right to vote for our own councilmembers.

Full text of the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative

Given the public reaction to the Council’s decision to appoint rather than hold an election, I reached out to Mayor Pro Tem Bill-de la Peña and Ventura County Supervisor Linda Parks about the prospect of guaranteeing future elections using the initiative process. The Council’s decision to appoint took place on February 21, and by the next day I had drafted a simple, six-sentence initiative, consistent with the options presented to but not chosen by the Council the night before.

Titled the “Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative,” the proposed law established findings that “[e]nsuring that Thousand Oaks City Council representatives have the support of the voters is a right of all citizens of the City of Thousand Oaks,” that “[p]revious instances of filling Council vacancies through appointment have led to outrage and distrust of the Council, undermining democratic and accountable government,” that “[t]he unchecked authority to fill Council vacancies through appointment has allowed a simple Council majority to handpick like-minded members in order to keep and expand their political power,” and that “[r]equiring that Council vacancies are filled through elections will guarantee the voters’ rightful place in the governing of the City and will prevent future abuse by any Council majority through appointment.” [90]

Consistent with what is allowed under state law, [91] the initiative established “[a]ll vacancies of the Thousand Oaks City Council shall be filled through election,” and that “if a vacancy occurs on the Thousand Oaks City Council,… a special election be called immediately to fill the council vacancy.” [92] The initiative also allowed the Council to fill the vacancy through an “interim appointment,” and that “this person will hold office only until the date of the special election.” [93]

To supporters, I described the petition as being “pretty simple - when a vacancy occurs, there will be an election, and the Council can make an interim appointment, who will serve only until that election.” [94]

The issue itself was popular but qualifying an initiative required contending with two logistical factors: navigating the process of submitting and qualifying the initiative, and the timing involved with qualifying the initiative for the ballot. While the Council appointment came in mid-February, the timelines were incredibly tight to put any measure on the November ballot.

“I believe in the right to vote, and I believe in elections,” I said in announcing the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative. “The Right to Vote Initiative ensures that the residents of Thousand Oaks will choose their own leaders in the future. It’s a positive step in the right direction.” [95]

After receiving the ballot summary from the City on March 23, our supporters were on the ground gathering signatures within a week, needing at least 10% of the city’s registered voters, [96] or 7,279 signatures. [97] In early May, Conejo Valley Days, the citywide weeklong festival, served as an opportune event to collect signatures reaching Thousand Oaks voters. I pledged to my volunteer group that I would collect 1,000 signatures myself during the festival. [98]

In my experience of gathering signatures for other initiatives such as open space protections and campaign finance reform, I had never collected so many signatures so quickly – a demonstration of the simplicity and popularity of the initiative. By the end of May, the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative campaign had collected over 10,000 signatures, which I had originally arranged to submit to the City for verification, but I delayed the turn-in event primarily out of respect for the family of Councilmember Tom Glancy. [99]

On May 14, Councilmember Tom Glancy, first appointed to fill the vacancy created from Ed Masry’s resignation in 2005, submitted his resignation due to complications from a rare form of cancer. Councilmember Glancy, who had served his country, the city, and the community for decades – a retired Navy captain, a member of the Rotary Club for 25 years, and six-year veteran member of the City’s Planning Commission prior to joining the Council – succumbed to his conditions on May 18. [100] [101]

Shortly after Glancy’s passing, the Council considered filling a vacancy for the second time that year, now in the midst of the Right to Vote petition drive. Speakers urged the Council not to consider an appointment and leave the seat open until November. Former Thousand Oaks Mayor Dick Hus addressed the Council, saying “The Council is faced once again with the challenge of filling a vacant seat on the Council. I believe that the Council should not only view this as a challenge, but also as an opportunity - an opportunity to demonstrate to the voters of our beautiful city that the Council recognizes and respects the right to elect citizens to serve on the Council.” [102] Noting that the Right to Vote initiative was nearing its completion in gathering signatures, I too urged the Council “to make the right choice for the voters and allow [the seat] to stay vacant, allowing the public to determine who fills that seat for the next four years.” [103]

Councilmember Fox, in recounting the challenge the Council faced in filling the earlier 2012 vacancy, defended his original appointment decision: “My first preference would have been to appoint for the remainder of this year and then have an election, but we were advised by the staff that because of the time limitations we would be running the risk of not being able to meet that obligation…[and] would have been borderline reckless in rolling the dice to try and fill two seats in the upcoming election, given the information we got from staff and the untimely resignation of Councilmember Gillette.” [104]

Mayor Pro Tem Bill-de le Peña believed the seat should stay vacant and criticized the process the Council pursued to date in dealing with previous vacancies. “We had the opportunity to also put Mr. Gillette’s seat on the November ballot; Council chose not to do that.” [105] The Council voted unanimously to leave the vacancy open without appointment and to be filled in November as previously scheduled. [106] A question remained about whether another initiative would also be placed before voters that November.

Staff presentation on Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative, Thousand Oaks City Council meeting, July 10, 2012.

Petitions for the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative were submitted on June 11 containing 10,421 signatures against the 7,279 signatures needed to qualify the measure and confirmed by the City to have contained 8,332 valid signatures. [107] When citizens present an initiative that has secured enough valid signatures, a local Council has limited options under California’s constitutional right of initiative. State law gives the City one of only two options which must be performed without altering the initiative ordinance: adopt the initiative ordinance, or submit the ordinance to the voters at the next general municipal election. [108] Prior to the meeting, a council can order an impact analysis report to study its fiscal impact and other matters that the Council request; the Council did request such an analysis on June 26, and, concerned over slanting the report, Councilmember Bill-de la Peña asked that the impact analysis report be balanced. [109]

The City presented its analysis, stating that “historically, there has not been a pattern of utilizing any particular method permitted under State law for filling unexpected Councilmember vacancies in Thousand Oaks,” and “there is nothing unusual nor different about how the past eight vacancies have been filled.” [110] The City’s analysis, however, didn’t differentiate the Council’s previous history of handling vacancies with the two events that created the need for the initiative in the first place.

“Since the short-term appointment in the earliest days of the City, holding elections to fill vacancies has been the historical pattern in Thousand Oaks,” I wrote. “The Council’s decisions in 2005 and early 2012 stand out as stark departures from the City’s historical pattern of filling vacancies by election.” [111]

When the matter came up for deliberation, numerous speakers addressed the Council, and I thanked the voters for signing the petitions and enabling us to have the discussion that evening. Mayor Irwin highlighted the common refrain, asking me about the costs of elections as “something that people are concerned about.” My reply went to the heart of the matter, saying “you oversee $200 million worth of money being brought in and spent every year, $66 million in your general fund every year, the cost of holding the most expensive election, which wouldn’t even happen every year, possibly every five or six years on average, would be $1.50 per resident. The question is: are we willing to invest $1.50 in every resident to guarantee the right so that we pick who sits there and spends all that money on a yearly basis?” [112]

While the costs of elections are commonly used as a rationale against holding elections at all, I responded, “Democracy has costs. People spend and pay far higher prices to ensure that we have the right where we elect the people who pass the laws in our city.” [113]

Upon Council debate, the change in rhetoric, if not a full change of heart, was evident. Councilmember Fox began by “thanking the speakers,” stating that their “sense of community and your sense of how we should be represented by elected government, I think it’s shared by everybody on the City Council.” Councilmember Fox did defend the Council’s previous decisions to appoint, highlighting that “the Council faced the very, very unusual circumstance where inside 60 days, we had two unanticipated vacancies…” [114] and that, as a result, “difficult choices” had to be made. While election costs are something the Council should consider, “I think the speakers put it correctly… all things being equal, representatives for the City Council should be elected,” Fox said. [115] [116] Fox moved to approve the initiative into law, saying that, as the inevitable result of a November vote on the measure, “I don’t believe it would be a divisive election.” [117]

Mayor Pro Tem Bill-de la Peña agreed, stating that “this is really the only option… Adopting the obvious is the right thing to do.” Mayor Irwin stated she would support the motion, but had “reservations,” defending her previous appointment votes. With the Right to Vote initiative, she said “future Councils will have less flexibility… and I do have concern about the costs, but the overriding thing is that the Council is supporting what the residents are bringing forth.” [118]

When the vote came, the Council unanimously approved the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote initiative into law, [119] and the decision was received with applause by those in attendance. [120]

Councilmember Andy Fox, after voting for appointments to fill previous Council vacancies, votes to approve the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative into law, July 10, 2012.

Mayor Jacqui Irwin, after voting for appointments to fill previous Council vacancies in 2005 and 2012, votes to approve the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative into law, July 10, 2012.

“More than 200 years ago, Thomas Paine [121] wrote: ‘The right of voting for representatives is the primary right by which other rights are protected.’ Yet, centuries later, we still find it necessary to fight for these rights,” I wrote after the passage of the Right to Vote Initiative. [122] “Voters should elect the people who represent them on the City Council. Voters can’t be considered “voters” unless they’re allowed to vote… I truly believe that if the council majority wanted to hold elections, they would have done so… Instead, the council majority continued to choose a darker path and provided numerous explanations, excuses, and justifications for doing so.” [123]

The Thousand Oaks Acorn praised the Council for making “the correct decision” in approving the initiative into law. “By supporting the measure, they took the first step toward repairing the public confidence that was shaken when they chose to fill [a Council vacancy] via appointment… despite three-plus years remaining on his term and a general election just around the corner.” [124]

“Since that time, Councilmembers Jacqui Irwin and Andy Fox, both of whom pushed for appointment, have publicly stood by their decision, but their actions—first choosing to leave the late Tom Glancy’s seat vacant and now supporting Right to Vote—are proof they were not deaf to the public rebuke. While we’d like to think their Tuesday votes were borne purely out of a change of heart, they made sense politically…[by making the issue] much less of a lightning rod.” [125]

Two years later, Councilmember Jacqui Irwin defeated Newbury Park evangelical pastor Rob McCoy for a seat in California’s State Assembly, creating a vacancy for her Council seat. With the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote ordinance in place, the June 2015 special election yielded a tight contest between McCoy and former Thousand Oaks Councilmember and Ventura County Supervisor Ed Jones.

On election night, Jones appeared to have garnered enough votes to win the open seat. By 11 pm that Tuesday night, the unofficial tallies had Jones leading McCoy by 75 votes, 5,769 for Jones and 5,694 for McCoy. [126] However, additional ballots still needed to be counted, and three days later, the results were official: Rob McCoy had pulled ahead of Ed Jones. 6,468 to 6,416, a margin of 52 votes, [127] the closest margin of victory in thirty years. [128]

In acknowledging the Right To Vote ordinance for his opportunity to represent the community, McCoy commended the residents of Thousand Oaks who chose “to not put up with an appointment but to elect an official.” [129] At McCoy’s swearing in, Councilmember Andy Fox noted that, even though the Council election was the only item on the June ballot, there was “by any measurable standard, a great turnout” in the special election, and Mayor Al Adam said to Councilmember McCoy that “you are living proof that democracy works.” [130]

In this chapter, unlike the 1994 episode when an election was held only because antidemocratic impulses were thwarted by an equal number of democracy advocates, the antidemocratic position now had the votes and no constraints, and a Council majority made the most of their newfound opportunity. They used their discretion to appoint their political allies to lengthy terms, not once but twice.

However, the people spoke and used the tools of Californian democracy to guarantee their roles in selecting city leaders; they strengthened their own place in our American democracy.

With the approval of the Thousand Oaks Right to Vote Initiative, the people made clear that, in Thousand Oaks, democracy is not discretionary.

There is one final topic. As we have seen, the cost of elections is regularly presented as a rationale for not holding elections; amazingly, it seems to surface without fail.

But is cost ever really an issue? It’s always raised in the moment, so let’s take a longer-term view.

The City of Thousand Oaks approves the biennial Operating and Capital Improvement Program budgets, covering anticipated appropriations and expenditures for a wide range of city services including water, wastewater, library, transportation, landscaping, street improvements, golf course maintenance, and various other programs. These budgets also include the General Fund, the chief discretionary operating fund for the majority of the City’s operations such as planning & zoning, community services and recreation centers, public safety, public works, and general administrative services. [131]

In reviewing the cumulative Operating and Capital Improvement Program budgets from 2000 through 2022, [132] a historical analysis over the past 22 years shows the following:

For every $300 spent in the City of Thousand Oaks Operating and Capital Improvement Program budgets, 5¢ is spent on our elections.

The cumulative Operating and Capital Improvement Program budgets between 2000 and 2022: $4.5 billion [133]

The cumulative General Fund budgets over this period: $1.75 billion [134]

The total spent on elections in the same period: $885,000 [135]

This means that for every $300 spent in the city’s total budget and every $100 spent from the General Fund, the amount spent on elections is about five cents.

One nickel.

As an affluent city in an affluent nation, we should be willing to spend at least a nickel on our own right to select our leaders. In a city that values our democratic ideals, the first nickel spent by government should be for the elections held so the people determine who spends the full $300 on their behalf.

Forgoing elections so that we can save half a penny should be dismissed as a viable argument. In a democratic America with free, fair, and open elections, there just are no good arguments to forgoing elections.

The right to vote is worth preserving and worth paying for.

[1] Thomas Paine, “Dissertation on First Principles of Government,” The Writings of Thomas Paine, ed. Moncure D. Conway (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1894; originally published in 1795), vol. 3, 267.

[2] One such article by Vanderbrouk is “Notes on an Authoritarian Conspiracy: Inside the Claremont Institute’s “79 Days to Inauguration” Report,” The Bulwark, November 8, 2021, https://www.thebulwark.com/notes-on-an-authoritarian-conspiracy-inside-the-claremont-institutes-79-days-to-inauguration-report/.

[3] Christian Vanderbrouk (@UrbanAchievr), Twitter, December 9, 2022, https://twitter.com/UrbanAchievr/status/1601240384054886400.

[4] Glenn Ellmers, “Leadership & Staff,” The Claremont Institute,” https://www.claremont.org/leadership-bio/glenn-ellmers/, retrieved December 10, 2022.

[5] Glenn Ellmers, “Hard Truths and Radical Possibilities,” American Greatness, November 23, 2022, https://amgreatness.com/2022/11/23/hard-truths-and-radical-possibilities/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Glenn Ellmers, “’Conservatism’ is no Longer Enough,” The American Mind, March 24, 2021, https://americanmind.org/salvo/why-the-claremont-institute-is-not-conservative-and-you-shouldnt-be-either/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Glenn Ellmers, “Hard Truths and Radical Possibilities,” American Greatness, November 23, 2022, https://amgreatness.com/2022/11/23/hard-truths-and-radical-possibilities/.

[11] California Constitution, Article II, Section 1.

[12] Miguel Bustillo, “The Man Behind the Money; Sizable Checks Testify to Attorney Edward L. Masry’s Readiness to Take a Stand,” Los Angeles Times, January 11, 1998.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Miguel Bustillo, “Zeanah’s White Knight Counters Pizza Queen,” Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1997.

[15] Kate Folmar, “Spending in Zeanah Recall Fight Topped $500,000,” Los Angeles Times, February 3, 1998.

[16] Resolution 2004-240, Thousand Oaks City Council, December 7, 2004.

[17] Kelley, Daryl, “Local Campaigns Keep It Clean, With a Few Exceptions,” Los Angeles Times, November 5, 2000.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Sue Davis, “Infection puts Masry back in hospital,” Ventura County Star, June 14, 2005.

[24] Jean Ortiz, “Masry aims to return to T.O. council in the fall,” Ventura County Star, July 18, 2005.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Jean Ortiz, “Activist calls for Masry to leave council,” Ventura County Star, August 17, 2005.

[27] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, Regular Meeting, June 21, 2005.

[28] Ortiz, “Activist calls for Masry to leave council”

[29] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, September 13, 2005, and October 25, 2005.

[30] Jean Ortiz, “Thousand Oaks Councilman Masry resigns,” Ventura County Star, December 1, 2005.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Sophia Fischer, “City Councilman Ed Masry resigns for health reasons,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, December 1, 2005.

[33] Catherine Saillant, “Masry Says Farewell to City Council,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 2005.

[34] Memo to City Council from Scott Mitnick, City Manager, and Amy Albano, City Attorney, “Subject: Filling Councilmember Vacancy: Agenda Item 4,” December 2, 2005.

[35] Fischer, “City Councilman Ed Masry resigns for health reasons”

[36] Memo from Mitnick and Albano, “Subject: Filling Councilmember Vacancy”

[37] Griggs, “Council to Name Masry Successor”

[38] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, December 2, 2005.

[39] Griggs, “Council to Name Masry Successor”

[40] Jean Ortiz, “Council to select person to fill seat,” Ventura County Star, December 3, 2005.

[41] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, December 2, 2005.

[42] “Don’t appoint, let voters vote,” Ventura County Star, December 11, 2005.

[43] Ibid.

[44] “The people should have decided who replaces Masry,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, December 8, 2005.

[45] Ibid.

[46] “Don’t appoint, let voters vote,” Ventura County Star.

[47] “The people should have decided who replaces Masry,” Thousand Oaks Acorn.

[48] “Don’t appoint, let voters vote,” Ventura County Star.

[49] “The people should have decided who replaces Masry,” Thousand Oaks Acorn.

[50] Douglas Martin, “Edward L. Masry, 73, Pugnacious Lawyer, Dies,” New York Times, December 8, 2005.

[51] Myrna Oliver, “Ed Masry, 73; Attorney Won Major Settlment from PG&E, Sat on Thousand Oaks Council,” Los Angeles Times, December 7, 2005.

[52] Martin, “Edward L. Masry, 73”

[53] Oliver, “Ed Masry, 73”

[54] Sophia Fischer, “City Council appoints planning commissioner to Masry’s seat,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, December 15, 2005.

[55] Gregory W. Griggs, “Thousand Oaks Council Names Masry Successor,” Los Angeles Times, December 15, 2005.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Grand Jury Final Report, Thousand Oaks City Council, F-38.

[58] Ibid, F-38, F-41.

[59] Ibid, C-01, C-03.

[60] Ibid, C-05.

[61] Ibid, C-06, C-08.

[62] Debate on Item 10A, “Filling Future Council Vacancy Options,” Thousand Oaks City Council, Video Archive, April 25, 2006.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Teresa Rochester, “Fixture leaving council in T.O. – Gillette cites health issues for resignation,” Ventura County Star, February 11, 2012.

[66] Letter to Jacqui Irwin, Mayor, from Dennis C. Gillette, Councilmember, February 10, 2012.

[67] Memo to Scott Mitnick, City Manager, from Linda Lawrence, City Clerk, “Subject: Filling Councilmember Vacancy,” February 21, 2012.

[68] Ibid.

[69] “How to handle Gillette’s vacancy,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, February 16, 2012.

[70] Ibid.

[71] California Government Code 36937(a). Additionally, the City of Oxnard enacted an exact ordinance of this kind on January 5, 2021, where the staff report noted that “ordinances relating to an election take effect immediately upon adoption and are not subject to the 30-day delay in effective date that usually applies to ordinances.”

[72] Debate on Item 9A, “Filling Council Vacancy,” Thousand Oaks City Council, Video Archive, February 21, 2012.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Teresa Rochester, “T.O. City Council appointment stirs controversy,” Ventura County Reporter, February 28, 2012.

[81] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, February 21, 2012.

[82] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, March 6, 2012.

[83] Debate on Item 9A, “Interview of Applicants for Councilmember vacancy and appointment of new Councilmember,” Thousand Oaks City Council, Video Archive, March 6, 2012.

[84] “The wrong decision,” Ventura County Star, February 23, 2012.

[85] Ibid.

[86] “Why do they fear a vote?” Thousand Oaks Acorn, March 1, 2012.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Inaugural Address of Governor Hiram W. Johnson Before the Senate and Assembly of the State of California, in Joint Assembly, at Sacramento, Tuesday, January 3, 1911 (Sacramento: State Office, A.J. Johnston, Supt. State Printing, 1911), 5.

[89] Spencer C. Olin, Jr., Prodigal Sons: Hiram Johnson and the Progressives, 1911-1917 (Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1968), 2.

[90] Ordinance No. 1580-NS, Thousand Oaks City Council, adopted July 17, 2012.

[91] Government Code Section 36512(c).

[92] Ibid., Thousand Oaks Municipal Code, Section 1-15.02.

[93] Ibid., Thousand Oaks Municipal Code, Section 1-15.04.

[94] Email from Mic Farris to Janna Orkney, “Subject: Re: Appreciation for the TO City Council Candidates and Comments on CC Bad Behavior,” March 8, 2012

[95] Mic Farris, Press Release, “Right to Vote Initiative Launched,” March 8, 2012

[96] California Elections Code, Section 9215.

[97] Memo to Scott Mitnick, City Manager, from Linda Lawrence, City Clerk, “Subject: Councilmember Vacancies Initiative Petition Certification, Impact Analysis Report, and Implementation Options,” July 10, 2012.

[98] Email from Mic Farris, “Subject: Conejo Valley Days and more…,” May 1, 2012

[99] Email from Mic Farris, “Subject: Postponement for Right to Vote Submission,” June 3, 2012

[100] Teresa Rochester, “Glancy steps down in T.O.,” Ventura County Star, May 15, 2012

[101] Teresa Rochester, “Ex-councilman Glancy, 71, dies,” Ventura County Star, May 19, 2012

[102] Debate on Item 9A, “Filling Councilmember Vacancy,” Thousand Oaks City Council, Video Archive, May 22, 2012.

[103] Ibid.

[104] Ibid.

[105] Ibid.

[106] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, May 22, 2012

[107] Linda Lawrence, City Clerk, City of Thousand Oaks, Certificate of Sufficiency for petition, July 5, 2012.

[108] California Elections Code, Section 9215.

[109] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, June 26, 2012

[110] City of Thousand Oaks, Councilmembers Vacancies Initiative, Impact Analysis Report, July 10, 2012

[111] Mic Farris, “Response to City’s Report on ‘Right To Vote’,” July 9, 2012

[112] Debate on Item 9A, “Councilmember Vacancies Initiative Petition Certification, Impact Analysis Report, and Implementation Options,” Thousand Oaks City Council, Video Archive, July 10, 2012.

[113] Ibid.

[114] Ibid. It is noted that the period between vacancies created by Gillette’s and Glancy’s resignations was larger than 60 days. Dennis Gillette submitted his resignation in a letter dated February 10, 2012, to be effective March 1, and the Council decision to fill the vacancy by appointment came on February 21. Tom Glancy submitted his resignation, which took effect immediately, on May 11, 2012. The period between vacancies was between 71 and 91 days, depending on when the Gillette vacancy was deemed to have been created.

[115] Ibid.

[116] Debate on Item 9A, “Councilmember Vacancies Initiative Petition Certification”

[117] Ibid.

[118] Ibid.

[119] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, July 10, 2012

[120] Debate on Item 9A, “Councilmember Vacancies Initiative Petition Certification”

[121] Paine, Dissertation of First-Principles of Government

[122] Mic Farris, “Farris: How city voters secured their rights in Thousand Oaks,” Ventura County Star, July 28, 2012

[123] Ibid.

[124] “Council makes right call,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, July 12, 2012.

[125] Ibid.

[126] Anna Bitong, “Ed Jones appears the winner by razor thin margin,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, June 4, 2015.

[127] Wendy Leung, “McCoy wins T.O. council post,” Ventura County Star, June 6, 2015.

[128] The closest race prior to the 2015 contest came in 1974 when Larry Horner bested Gregory Kampf by 37 votes for his first of four terms on the Council.

[129] Anna Bitong, “Pastor’s prayers answered,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, June 11, 2015.

[130] Debate on Item 4A, “June 2, 2015 Special Municipal Election to fill City Council Vacancy Results/Swear in New Councilmember,” Thousand Oaks City Council, Video Archive, June 23, 2015.

[131] “City of Thousand Oaks, California, Operating Budget, Fiscal Years 2021-2022 & 2022-2023,” City of Thousand Oaks, adopted June 8, 2021, viii-ix.

[132] City of Thousand Oaks Operating Budgets from 1999-2000 to 2022-2023, example - “City of Thousand Oaks, California, Operating Budget, Fiscal Years 2021-2022 & 2022-2023,” City of Thousand Oaks Annual Budgets (Historical), https://weblink.toaks.org/WeblinkPublic/browse.aspx?id=302950&dbid=0&repo=CTO, retrieved December 10, 2022.

[133] Ibid.

[134] Ibid.

[135] City Council agenda packets and meeting minutes listed approved and/or budgeted expenditures for conducting election activities, such as contracting with Ventura County to run municipal council elections, conduct votes on local initiatives, and incur costs associated with candidate forums in City facilities. Sources include agenda packets from June 8, 2000, June 13, 2006, and June 5, 2018, and minutes from Thousand Oaks City Council meetings from June 4, 2002, June 8, 2004, December 18, 2007, February 5, 2008, March 18, 2008, June 10, 2008, May 25, 2010, December 7, 2010, March 22, 2011, May 22, 2012, July 10, 2012, June 10, 2014, December 9, 2014, March 24, 2015, May 24, 2016, June 28, 2016, June 9, 2020, and May 24, 2022.